FELLOWSHIP AMONG BLACK MEN IN EDUCATION IS A NATURAL, TIMELESS BROTHERHOOD

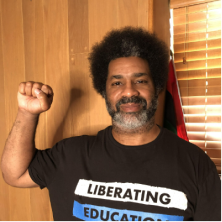

SHARIF EL-MEKKI, FOUNDER/CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER

CENTER FOR BLACK EDUCATOR DEVELOPMENT

There’s a racist, classist narrative that Black men in education defy. This damaging narrative presupposes a “get mine” ethos, particularly among individuals who are poor—which is still, too often, a stand-in for “Black” in our country since Black Americans are disproportionately poorer than any other racial group in this country.

But this “get mine” mentality can’t and doesn’t exist among Black men in education. Instead, what drives each one of us, and the collective, is a proud and sincere concern for each other’s welfare and success. Rather than “get mine,” we employ a unifying collective-responsibility mindset. Rather than “get mine,” “we lift as we climb.”

As I was beginning my career as a teacher at John P. Turner Middle School in the early 1990s, it was a rare fortune to have not one, but two, Black men in education, Dr. William “Bill” Blackwell and Mr. Robert “Bob” Gibbs, to guide me to my rightful future.

Even before then, Baba Changa, my all-time favorite teacher, an instructor of political science, history and Vita Saana martial arts, presented a bright mirror to what was possible for me as early as second grade. He saw in me a younger version of himself, and I saw in him a brilliant, committed and revolutionary Black male role model. I wanted to become someone like him.

So, when I became a principal years later, it was only natural to mentor others as I had been mentored.

Young Black teachers just beginning their careers would reach out to me. They’d ask, “Can we meet? I want to discuss my vision and plans for the future.” Others would ask, “Can we get coffee? I’m thinking about quitting.” Each time I’d hear that, my heart would sink. You can’t get used to hearing social justice warriors telling you there was no one they could talk to in their schools, and that they were at the end of their ropes.

As brave and committed they are, some Black male educators still have a hard time fighting back the microaggressions of a racist culture so firmly embedded into the public school system. Others aren’t weary from the fight for justice, but if they have a community behind them, they’d be even more powerful.

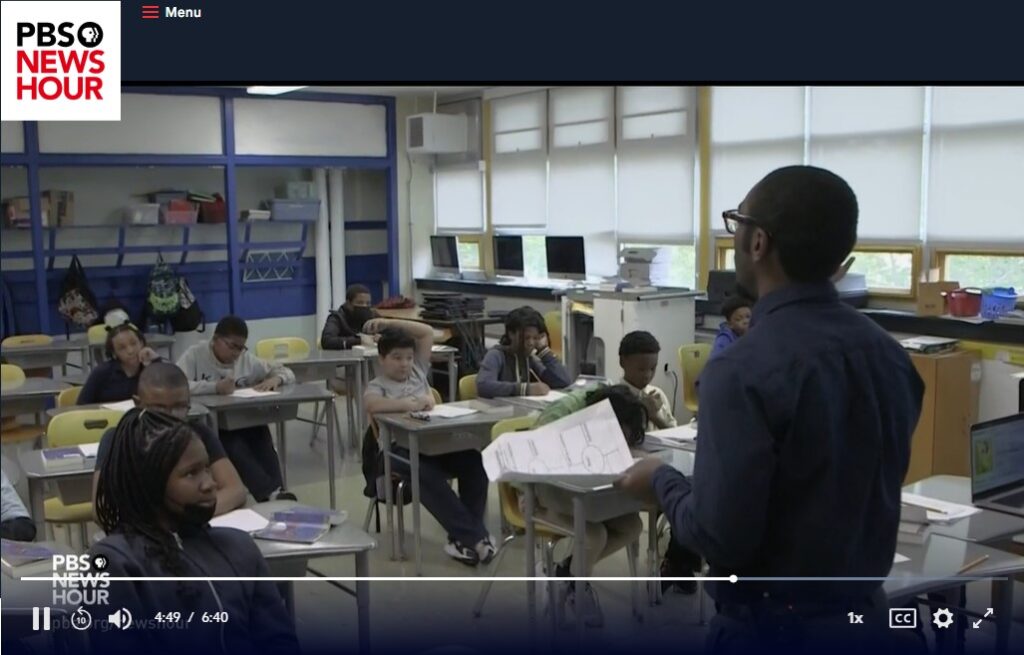

Men like Robert Parker, who was, at the time, a new teacher who inspired me and reminded me of myself starting out as a new teacher. Serious and thoughtful, Robert is a community activist compelled to integrate his considerable knowledge of Black history and relentless fight for social justice into his classroom instruction.

When Robert and I’d meet, we’d talk about his wins and struggles, coming up with possible solutions together for him to try. We also got to know one another and our families. I was thrilled to find out that he had married one of my favorite students from my teaching days at Turner Middle School.

But then I got more calls and started to make many more connections. James Brooks IV, Clayton Carothers IV, Vincent Cobb II, Rashiid Coleman, Julian Falana, Sterling Grimes, Vance Lewis, Chris McFadden, Malik Nelson and Raymond Roy-Pace among others. All urgently asking to meet.

I never said no, so before I knew it, there were ten young Black male educators I was regularly meeting with. Sometimes over coffee, lunch or dinner—almost always at a Black-owned establishment, and always for at least a couple of hours.

I was so pleased to discover that several of these young men—James, Clayton, Julian and Raymond already knew each other from working together at Lindley Academy Charter School at Birney, where Black male educators at one point comprised almost 60 percent of the entire faculty. Unheard of, not just here, but nationwide.

These young men, “the Birney Brothers,” represented remarkable Black men in education inside a school as a result of the forward-thinking vision of a renegade Chief Academic Officer, Dr. Bernard X. James, Sr., who took on an active role in the recruitment and retention of Black male educators.

James was working at Watoto, an afterschool program, when he was personally recruited by Birney Principal Debbie Durso. I was grateful to be able to hire Clayton and others from Birney for my own school, Mastery Charter—Shoemaker Campus, all of whom had been bolstered as novice educators by this school community that made peer support possible for Black male educators.

As these multiple monthly one-on-one sessions kept happening, things got to a point where I knew I couldn’t keep up this intensive mentoring and still devote the attention and energy required of my “turnaround school” (a designation for the lowest-performing schools in Philadelphia that require major intervention)—let alone to my family and friends outside of this rapidly growing circle.

So, I put a call out to my peers—other Black men in education who were already seasoned professionals with decades of experience in the field. Friends in the profession: Charles Adams, Aaron Bass, Joseph Ferguson, Dr. William Hayes, Tremaine Johnson and Miles Wilson. Others with whom bonds quickly established: Maurice Johnson, Benjamin Lewis and Jonathan Walker, among others.

All like-minded and like-hearted education leaders in Philadelphia who were also consistently and independently mentoring young Black educators in their own spaces. The response from each and every one was quick, positive, appreciative and profound. There was no convincing required, no need for cajoling or teeth-pulling. They were there from “Hey, man.”

To be clear: the reason my peers responded so immediately, without question, to the call for fellowship was not because it was me who made the call. These busy, sought-after educators and community leaders responded because it tapped into, for them, a powerful and empowering collective responsibility already consistent with their character, outlook and daily lives.

For us, coming together to help younger men in the profession was the natural order of things. It made sense. For us, it wasn’t just the right thing to do, it was the necessary thing to do in our respective fights for social justice.

What followed was a series of regional convenings. Group discussions were difficult and enlightening, supportive and solutions-oriented. Topics included: Black men in education and stereotype threat; career burnout resulting from our adoption of the fireman’s mentality of diving into the biggest fires, where we are needed most; and many more tough matters made tougher when you have to overcome them in isolation without resources nor support.

It was important for the fast growing group to build a common lexicon of references, including research findings, influential people and like-minded efforts. All to make each of us stronger and our nascent brotherhood armed with the intellect and knowledge in the fight for educational and social justice.

We exchanged reading material, including those on Black history and pedagogy, important studies, information about professional development, upcoming events, job openings and funding opportunities. We’d also participate as a group in studies, encouraging Black male educators to complete surveys and engage in related research.

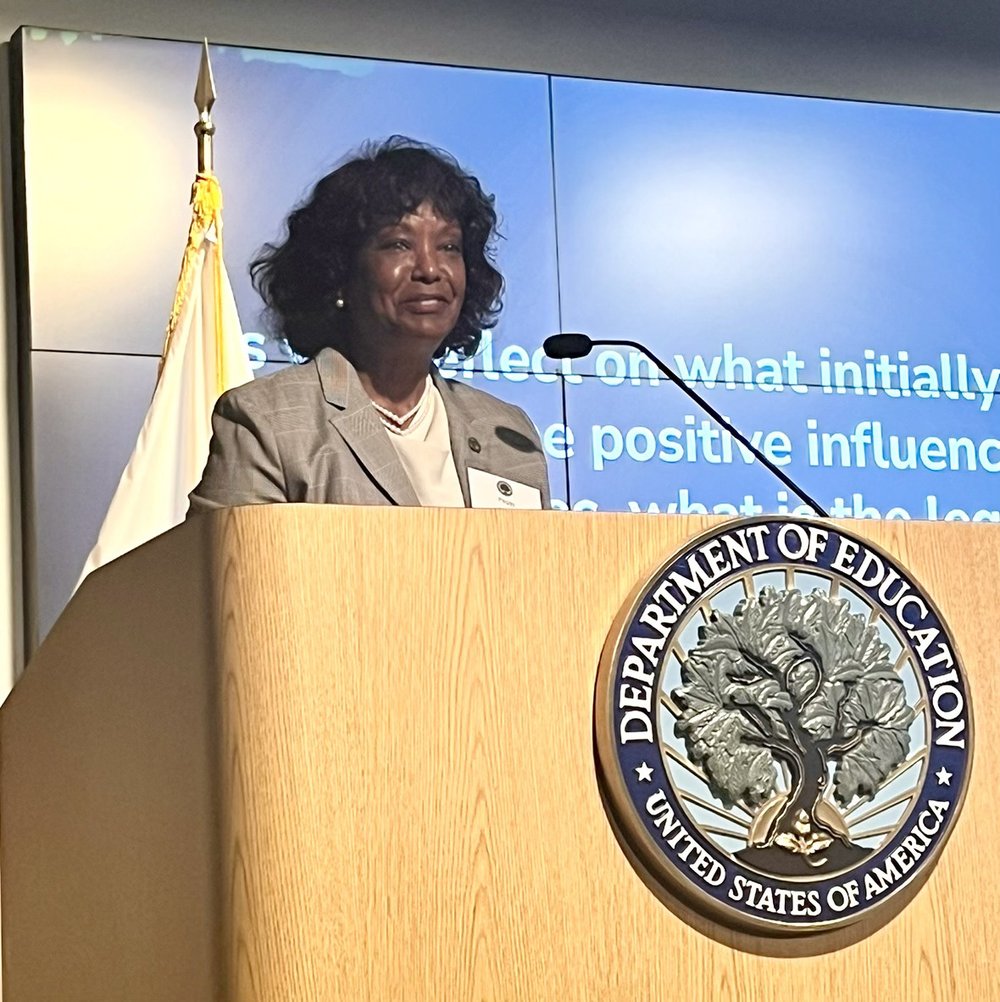

A high point of those early days was the trip we organized to go to Washington, D.C. in May 2015 to attend the first-ever national Male Educators of Color Symposium, hosted by then U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan and led by Jenese Jones with support from education leaders, including David Johns and Dr. Khalilah Harris, both of whom served on the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for African Americans.

Members would also present their focus and related projects to gather support, resources and more connections.

- Dr. Hayes, who brought great dynamic operational expertise to the group as a school administrator, leaned on our fellowship to rally support for the national Black Male Educator Alliance (BMEA), a national network of Black male educators with chapters in Illinois, Michigan and Washington, D.C., respectively led by Dr. Curtis Lewis (Chief of Teaching and Learning at Henry Ford Academy in Detroit), Gene Pinkhardt (a longtime educator and leader from D.C. who now leads the Aspen Education urban district networks) and Dr. Hayes. Early on, BMEA presented a great model for what we were trying to do in Philadelphia.

- I was introduced to Vincent Cobb through Mary Lema at the Teach for America Philadelphia branch. Cobb had been hired to work on a grant project (that was ultimately not funded) to increase the number of Black men in TFA’s local teacher corps.

- Raymond Roy-Pace, the current Assistant Principal at Lamberton Elementary School and the member who introduced the fellowship to the Birney Brothers, conceptualized and led our ”Why I Teach” tour for high school and college students in order to fortify our Black educator pipeline building efforts.

- Aaron Bass, a fellow Philly-born-and-raised school administrator, led the effort to take a group of students to the Justice or Else Rally on the 20th anniversary of the Million Man March.

With each subsequent convening, as word got out, the numbers continued to grow among both younger and older Black men in education. Throughout, we supported and were supported by one another, whether it was exchanging teaching strategies, serving as job references or making recommendations for grant support.

We soon came to know we weren’t alone in our struggles and triumphs. Our fellowship became a known and knowable community.