Schools can’t just hire teachers — they must keep them. Here’s how.

by Sharif El-Mekki, For The Inquirer

As the new school year dawns on Philadelphia, it brings with it both challenges and opportunities for schools and their leadership.

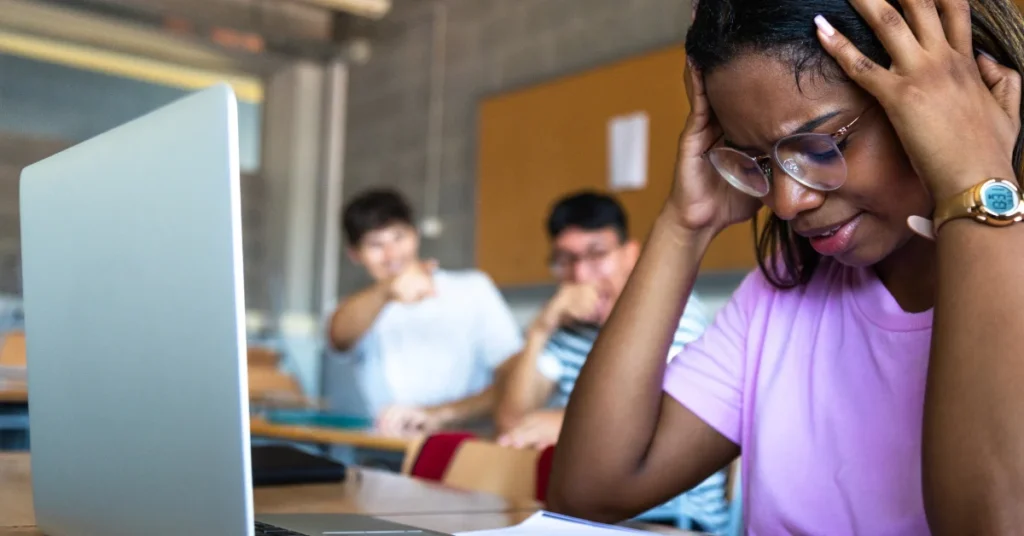

This summer, new research found that teachers are leaving Pennsylvania schools at increasingly high rates, and Philadelphia’s public schools are the hardest hit. In the city, more than 15% of teachers quit each year.

That level of staff turnover is difficult to manage in even ideal circumstances. In our most challenged schools, where attrition rates can be even higher, it can be paralyzing.

When a school has high staff turnover, that is an indictment of its leadership. As they say, staff don’t quit their schools, they quit their principals.

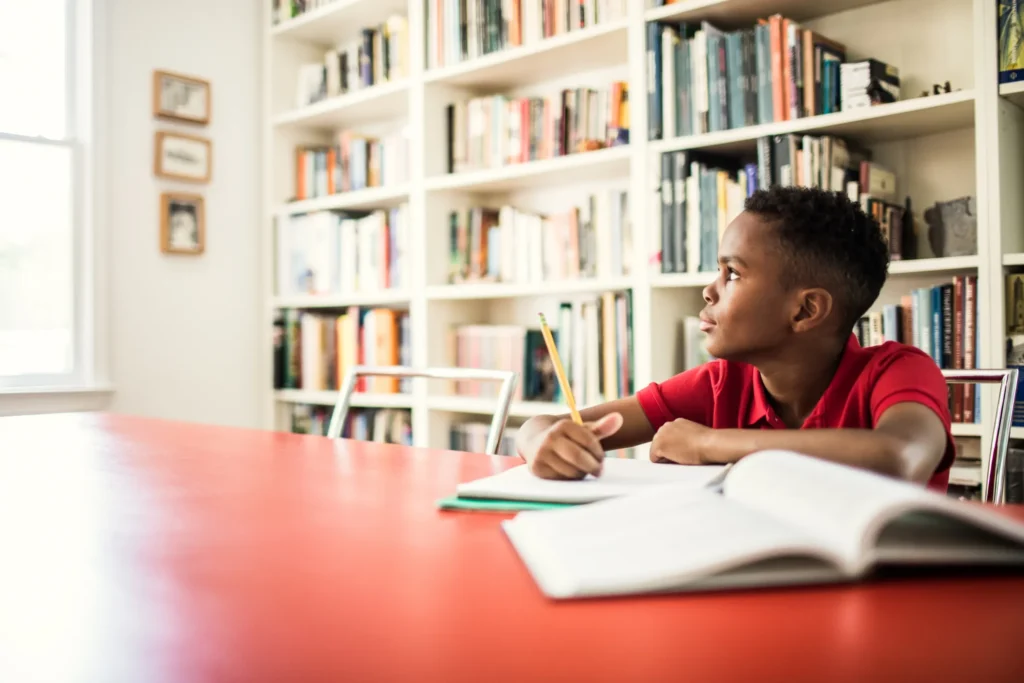

Now the first week of school has arrived, regardless of the headwinds our leaders face. Recruiting staff to plug vacancies is necessary, but not sufficient to deliver the kinds of educational experiences our students need, the kinds of learning environments that will close achievement gaps in our city.

School leaders must approach the new school year with retention in mind — meaning, not just finding someone to fill a vacancy, but finding the right person, and creating an environment that makes them want to stay in the job.

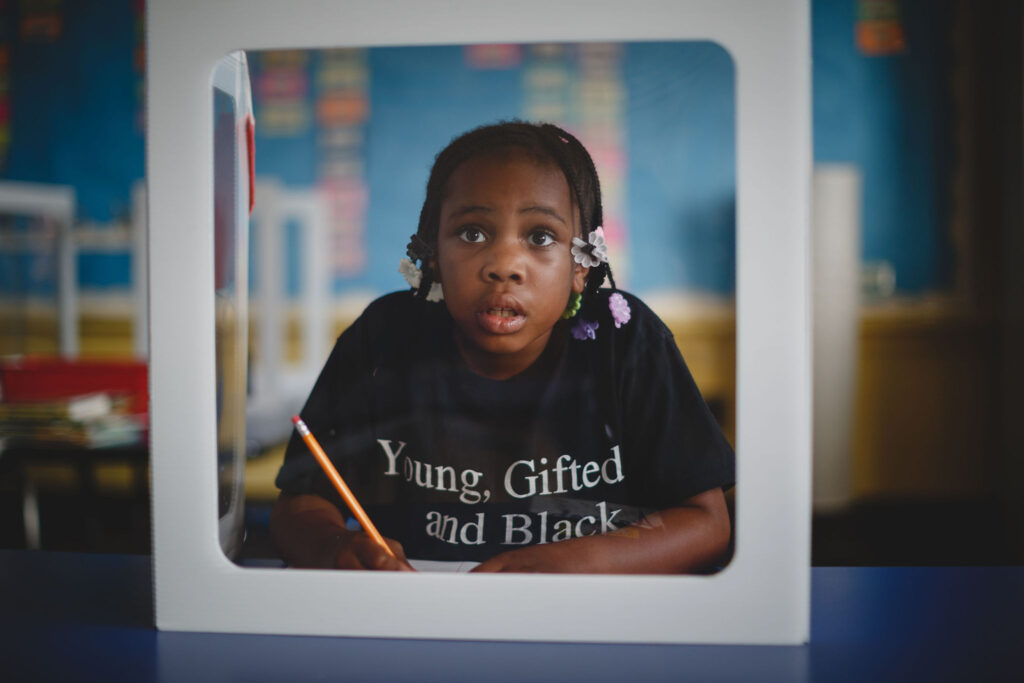

Keeping teachers happy has many benefits, beyond improving retention. Students can tell the difference between teachers who are invested in a school and those who are looking for a way out. If teachers are in it to win it, students are more likely to be as well.

Keeping teachers happy has many benefits.

To create an environment that fosters teacher retention, schools must be intentional about their learning ecosystems.

Here’s how.

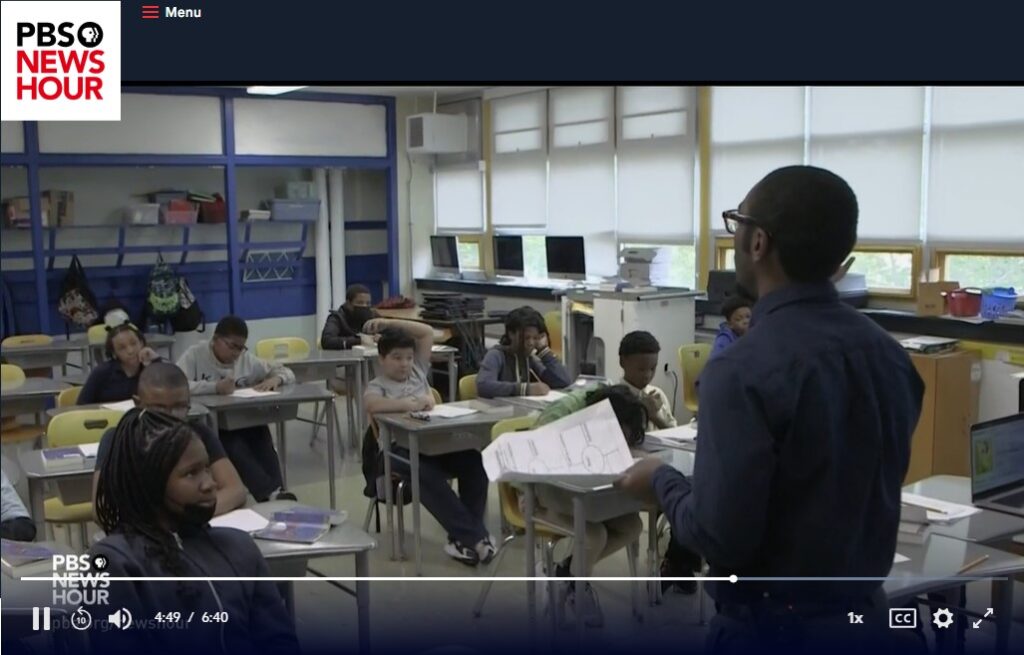

This school year, principals and other administrative staff should focus on proactively building relationships with their students, other staff, and school communities. You can’t lead from behind a computer or a closed office door. Being among students and staff — in classrooms, hallways, and break rooms — gives leaders a different vantage point that can inform all that they do.

But it’s more than that. Leaders should get out and engage, not just in the school, but in the community that their students call home. That means shopping at neighborhood businesses, knowing the folks in the community in personal and meaningful ways, and seeing the school as part of a broader whole.

When I was a principal at Shaw Middle School (now Hardy Williams Mastery Charter School), a neighbor connected us to a community group that helped our dance teacher secure new uniforms for our students and raise funds to transform a dilapidated classroom into a dance studio. At Mastery Charter School — Shoemaker Campus, local faith-based leaders would check in on students during the year and sometimes attend back-to-school nights. A local barber gave free haircuts to students who reached their reading goals.

Second, leaders who lead with vulnerability are more effective. People don’t want a leader who comes off as indestructible or unflappable; they want to follow leaders they actually know, who have empathy, and who themselves can relate to the real challenges of being a teacher, student, and, well, person.

This took me a while to realize. When I was working as a principal, I asked a colleague and friend for feedback, and they let me know that even though our colleagues knew my dedication to students and the work, they felt they didn’t know me as a man and leader. I started being a little more open about who I was as a human being — talked more about my family, my community, my upbringing, my daily struggles — not just my educational philosophy and orientation. Once I started doing that, I noticed that it was easier to work with school staff when challenges arose, likely because they had more trust in me. It made our team stronger.

Third, while school leaders put out the fires that invariably fill their days, they also have to think long term — and include students and staff in that vision, so that everyone owns it and will feel accountable to see it through. While a principal at Shaw, I made sure the staff were an integral part of creating and realizing a positive, anti-racist culture. Leadership duties were spread around the staff, even while I held myself accountable for student outcomes. During my time there, the percentage of kids performing at grade level increased, and our school library (a rarity to have even in those days) was stocked with affirming and informative books and materials.

As a former principal, I often encourage school leaders to be courageous. Don’t be afraid to fail or be fired on behalf of your kids, your staff. Do the right thing by the community you serve, both within the school walls and adjacent to them. Focus on how you can do what needs to be done so that you can be of service to them. Because ultimately that’s why you got the job in the first place.

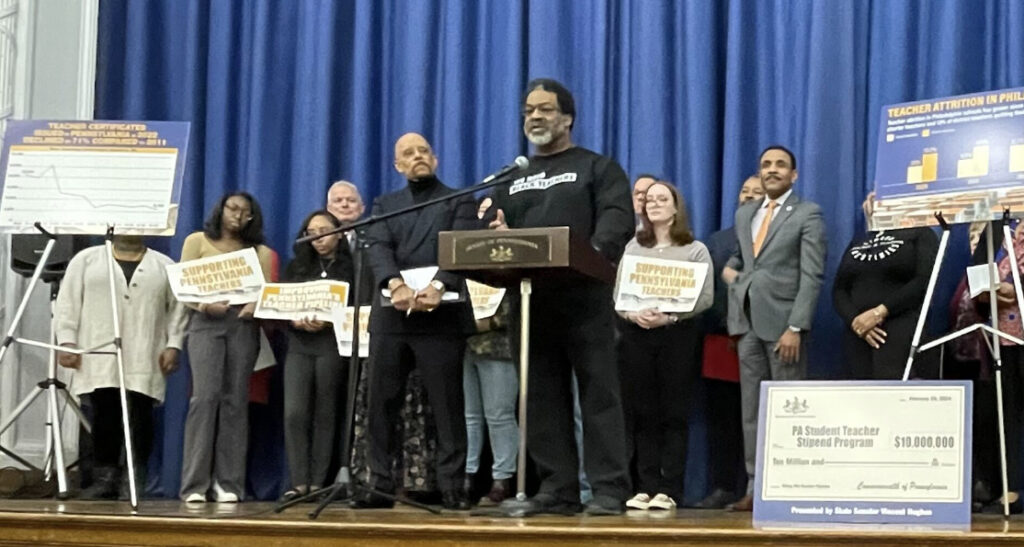

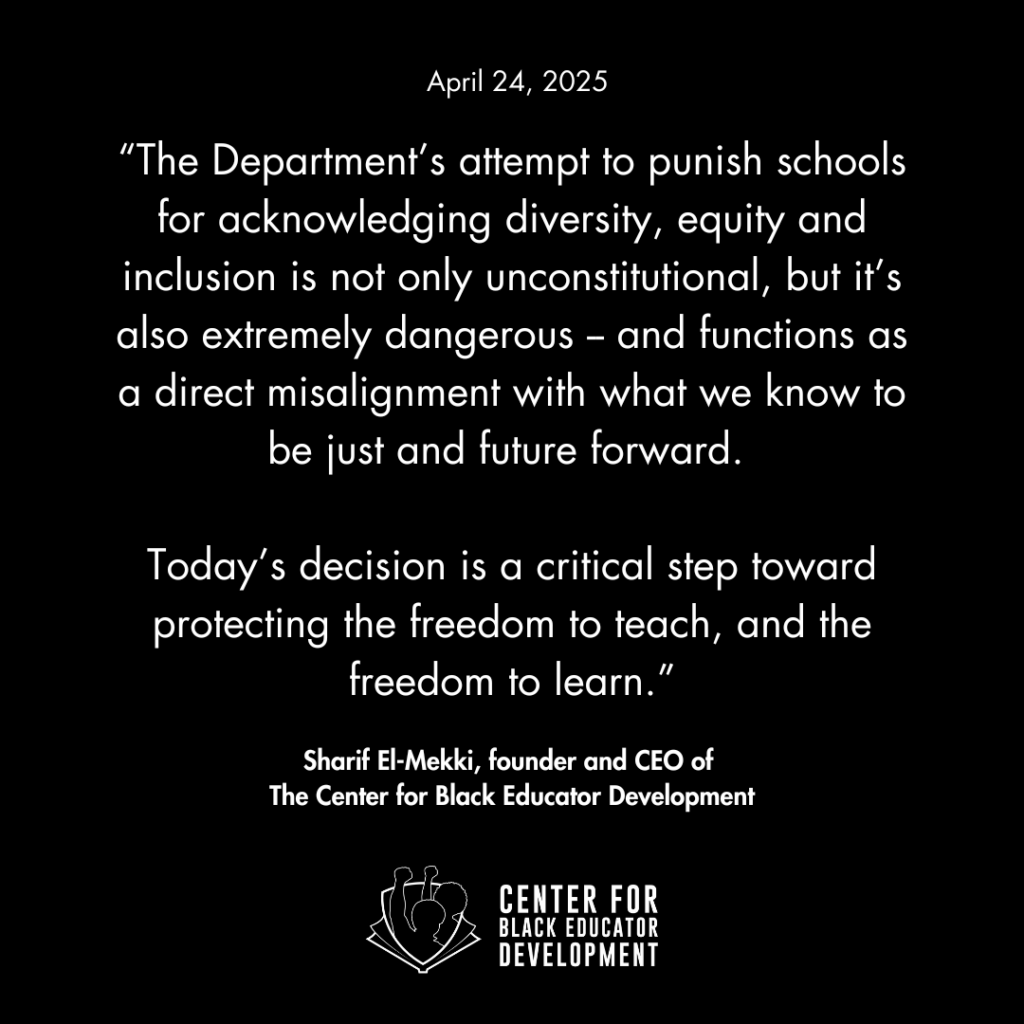

Sharif El-Mekki leads the Center for Black Educator Development. He was a teacher and principal in the School District of Philadelphia and is the former principal of Mastery Charter School — Shoemaker Campus. He founded the Fellowship — Black Male Educators for Social Justice, is a member of the “8 Black Hands” podcast, and blogs at Philly’s 7th Ward.