Black teachers are burning out of classrooms. Meet the people fighting to keep them there

Here are a few programs offering professional development, community, and support to Black teachers in the summers and throughout the year.

By Rebekah Sager for The Reckon Report

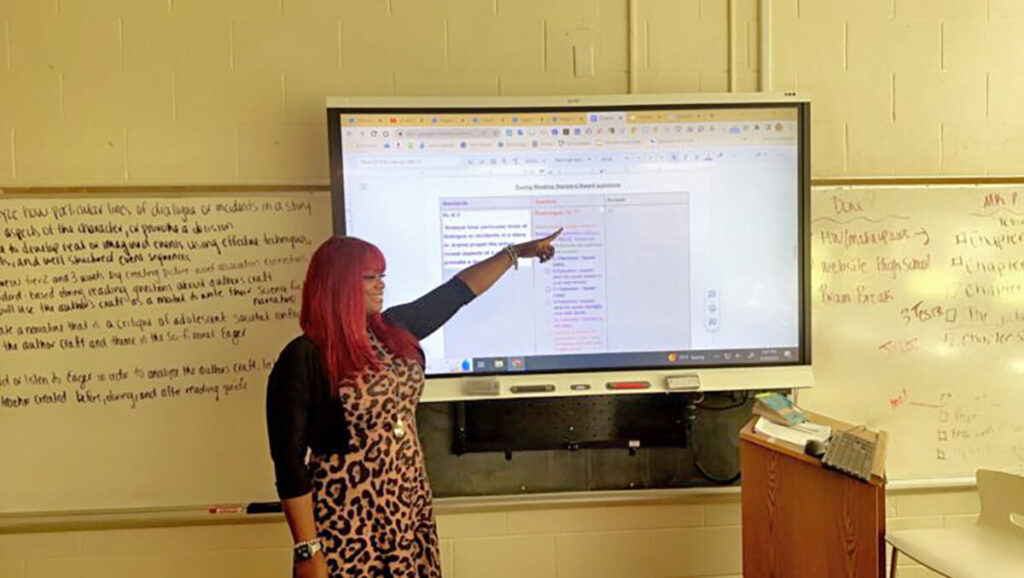

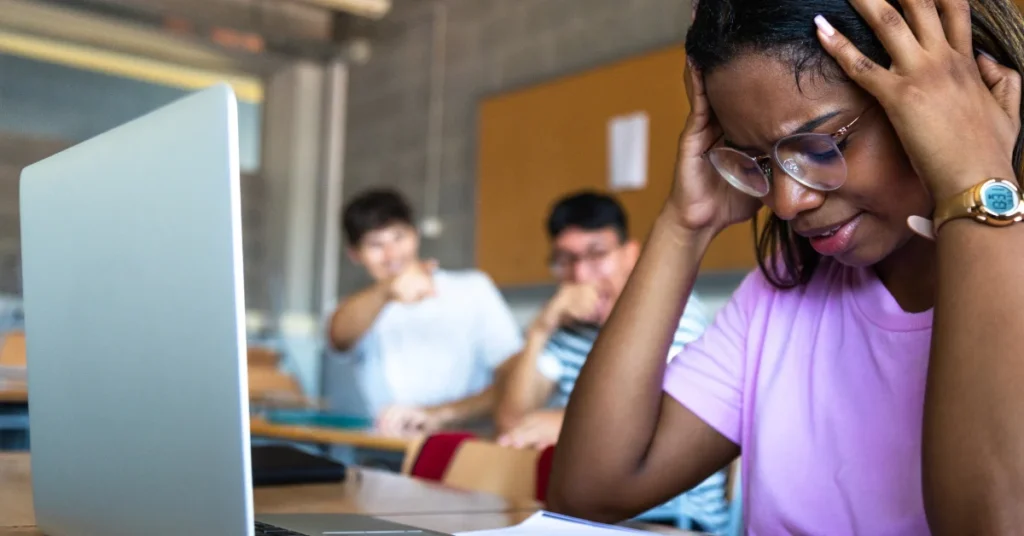

As educators head back into schools, not only will they face the normal challenges of the classroom, but Black teachers, in particular, will face additional stressors — being the only ones in their schools or districts, political pressures of book bans, and even requirements to teach a curriculum that is either outdated or erases the realities of Black history and culture.

Very few, if any, school districts offer professional development, retreats, workshops, or conferences targeting Black teachers. Yet, programs like these are essential for these teachers to connect with one another and sustain their mental well-being. Programs such as these can ultimately make the difference between whether they stay in the profession or not.

The percentage of Black teachers in the U.S. pales compared to that of white teachers — only 7% identify as Black, and only 2% are Black men. According to a report released by the RAND Corporation, in 2021, Black teachers were two times more likely to leave the profession than their white colleagues. In a recent survey of U.S. teachers published by RAND in June, Black teachers reported higher rates of burnout than white teachers and were more likely to leave their jobs. So, things are only getting worse.

The good news is that more programs for Black educators are popping up. Programs such as the Black Male Educators Alliance, which focuses on professional development and support for Black male teachers, the Black Teacher Project, which offers teacher meet-ups and wellness programs, the Black Male Educators Talk (BMEsTalk), which offers in-person workshops and year-round programming, and Black Lives Matter at School, a project that works to “address racial justice in education by promoting restorative justice, advocating for mental health support, increasing Black teaching staff, ending police presence in schools, and mandating Black history and ethnic studies.”

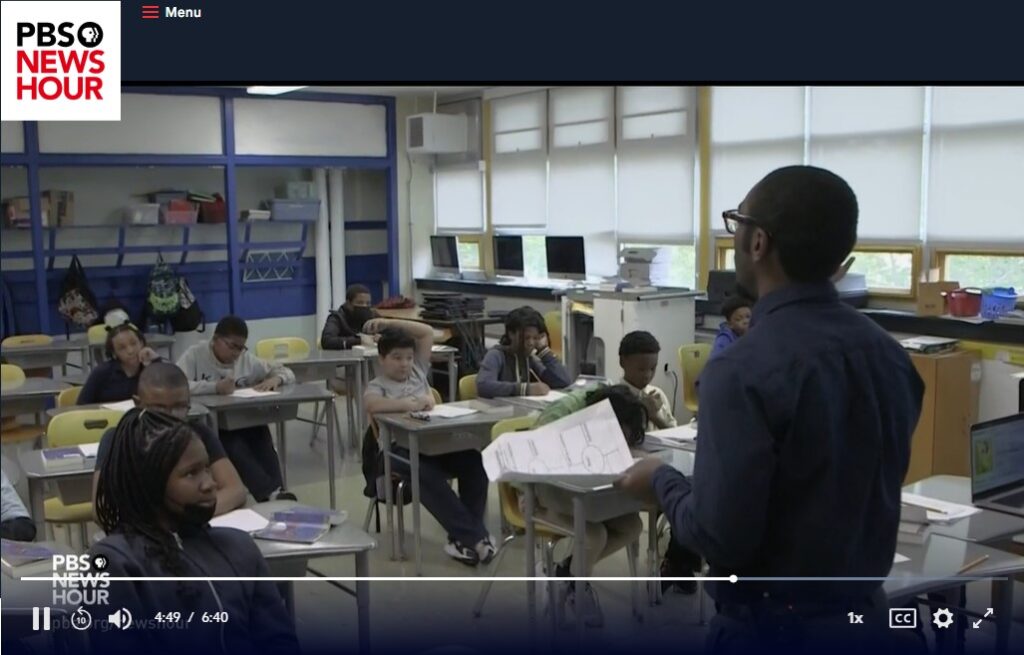

Ismael Jimenez, director of the social studies curriculum of the School District of Philadelphia, is a co-founder of the Black Lives Matter at School program. He tells Reckon that the program is a great place for Black teachers to network and learn about new topics.

“When you’re in the space, especially like this virtual space of teachers not just from Philadelphia — we do have folks from Kentucky, Buffalo, and Florida, who tune in — it becomes kind of like a community,” Jimenez says.

“We cover subjects that folks have never even been exposed to before. Like, one of the first reparations movements in America [which] was led by a woman named Callie House. We had a teacher even present on her life and legacy and how she teaches about her in her class and how that extends to the current conversation around reparations,” Jimenez adds.

Micia Mosely is the executive director of the Black Teacher Project. Her programs are all based in the Bay area of California and Atlanta, Georgia. She tells Reckon she’ll have some “back to school” meetups in the fall as well as other programs.

“The first weekend in November, we’re having a wellness retreat in Atlanta. And so that’s the big event, and that’s in person over two days. … And then June of next year, we’ll do our Leadership and Sustainability Institute. And the sustainability component of that institute is very much focused on mental health,” Mosely tells Reckon.

Mosely’s Leadership and Sustainability Institute will take place in the Bay area. The group will host a Hiring & Sustaining Black Teachers virtual workshop on Dec. 5.

She adds that the Black Teacher Project advisory board also plans to offer grants to teachers focused on therapy. The money will come from donations to the organization and go directly to teachers to offset the cost of therapy or other mental health support.

“What I’m excited for and what I hope for the teachers involved with Black Teacher Project is that they are able to find and sustain community in that way as much as we’re trying to go back to in-person events,” Moseley says.

“We always want to remember the folks who are isolated and remind them that they may be physically isolated, but in terms of community, they are connected.”

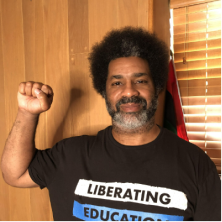

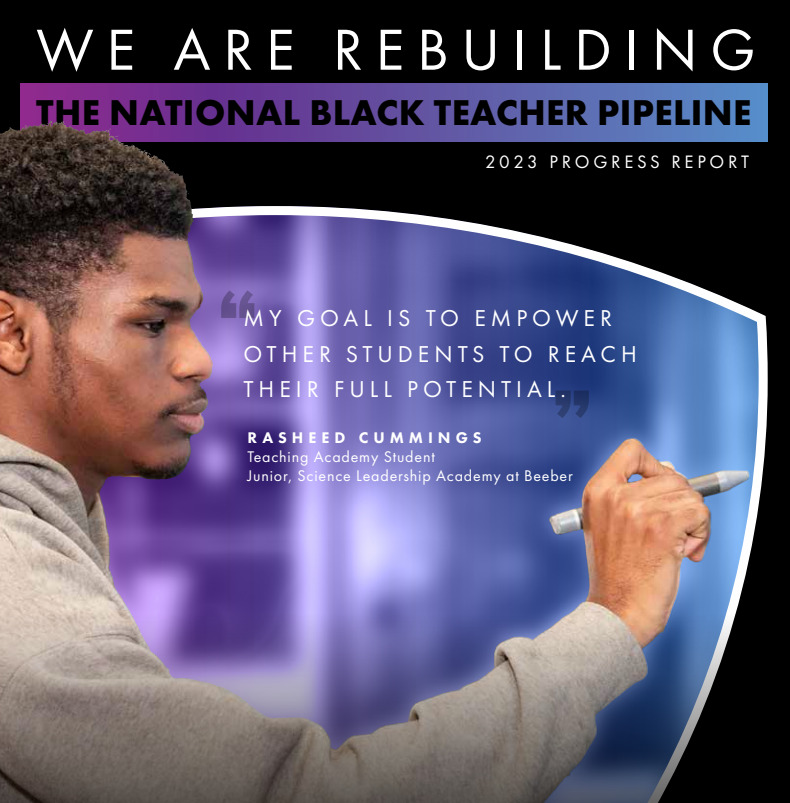

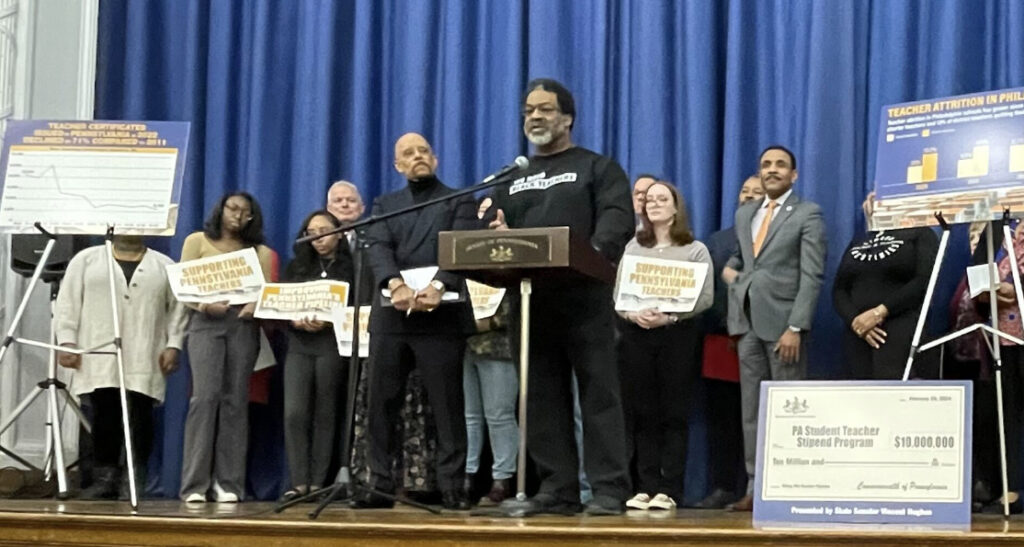

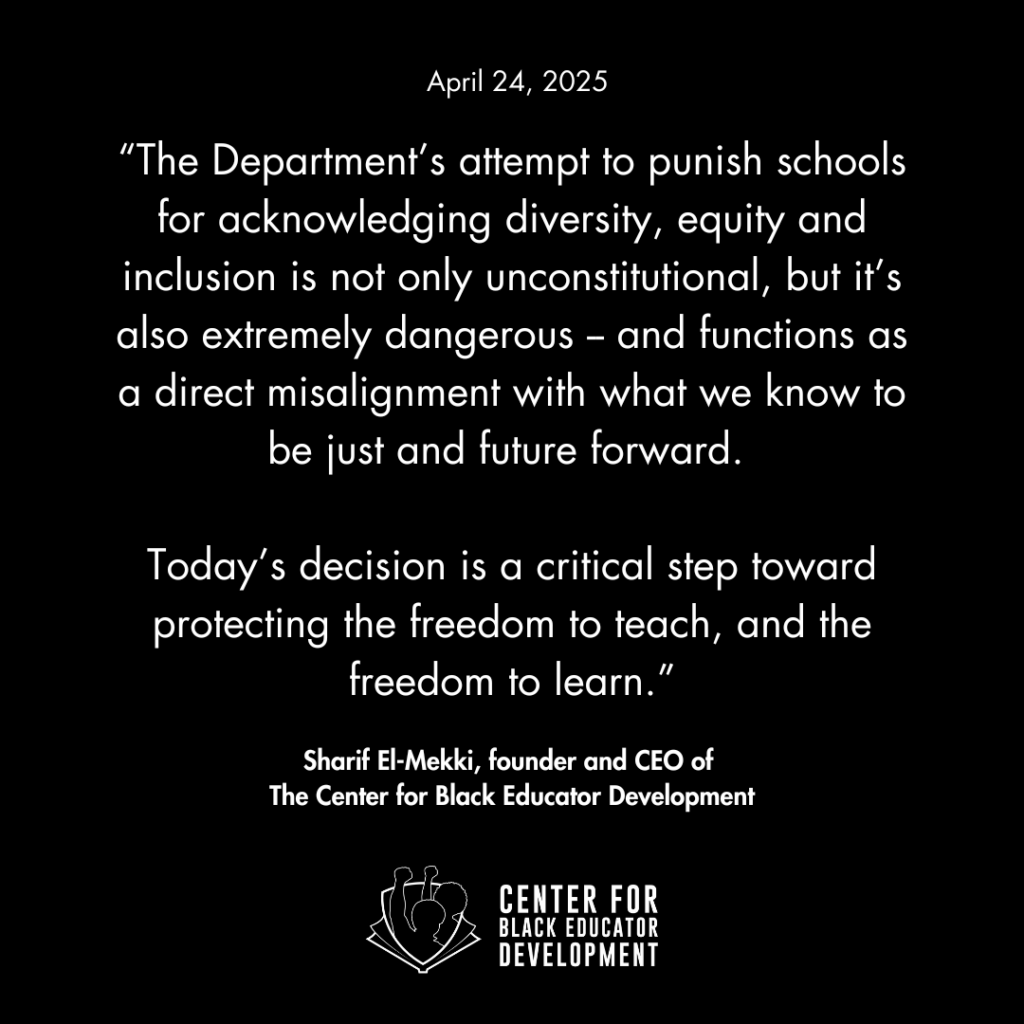

Sharif El-Mekki, director of the Center for Black Educator Development, tells Reckon that when teachers gather in retreats, conferences, or meet-ups, it’s vital to their growth as teachers, but also their mental health - even during the school year.

“People have expressed a tremendous appetite to not only have that convening. … Both for the affinity space and the professional development, but even more importantly for community.”

El-Mekki adds: “We have people there who are the only Black teacher in their district, which, growing up in Philadelphia, is still mind-boggling.”

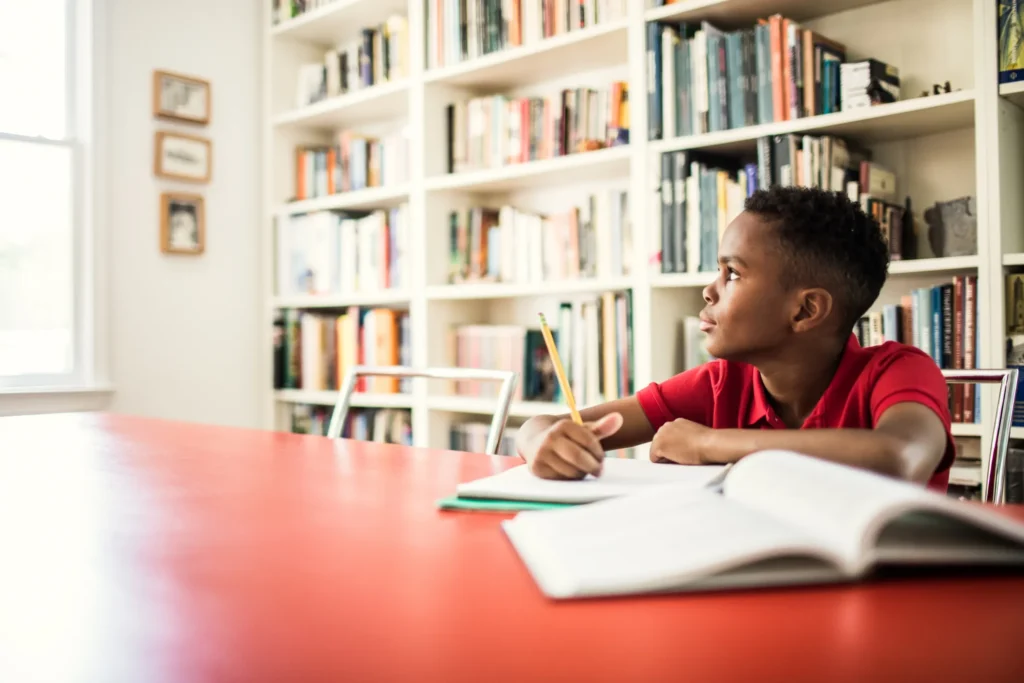

The Black population in Philadelphia is around 654,000 out of the total population of 1.5 million. But, only 24% of the teachers in the city are Black, and only 4% are Black men. According to EdTrust, 14.5% of students in Pennsylvania are Black, but only 3.8% of the teachers are Black.

Ayodele Harrison is a senior partner with Education with CommunityBuildVentures, a pro-Black community of facilitators, coaches, and strategists who are committed to supporting organizations and leaders by understanding, embracing, and embodying racial equity.

Harrison leads an initiative with Black male educators that focuses on enhancing teacher wellness, social and emotional development in students, teacher retention, development and advancement, and learning about supplemental income streams.

“Black men educators talk started in 2017 as a Twitter chat. It came out of the need for wanting to be in the digital space and hold conversations,” Harrison tells Reckon.

Since then, the group added its first in-person event and launched a two-part leadership model with support from a grant from the New School Venture Fund.

Abigail (she prefers we use only her first name) has been teaching African American History for the past 10 years. This summer, she participated in and presented at the Teaching Black History Conference in Buffalo, New York, in mid-July. This year’s theme was “Hip Hop.”

“I went last year. And that was amazing because you were just surrounded by a bunch of people who are interested in teaching Black history no matter what. And it’s just a good way to meet,” Abigail says.

Abigail is also participating in a research project focusing on Black teacher retention. The group meets three times a month on Zoom to consider what they want the project to focus on.

“It’s been just really wonderful because it’s been making me think about my own value as a Black teacher. And it’s just been really nice to hear there’s somebody in that group that’s been teaching for over 20 years, and then there are two people in the group that quit after three years. So there’s just quite a range of Black teachers who are participating in that, and it actually doesn’t feel like work, even though we’re getting paid to participate,” Abigail says.

In November, El-Mekki’s group, Black Male Educators Convening, will celebrate its sixth year.

“In 2014, we started convening Black men who had been reaching out for support, for need of community, for need of an intergenerational relationship with veterans, as well as that ‘lift as you climb’ mantra that we use often. … Last year, we had about 1,000 people there, the vast majority of them Black men, who said this was just a critical space for them to feel sustained, to feel supported, developed, coached, and mentored,” El-Mekki says.

Dr. Curtis L. Lewis is the Founder and CEO of the Black Male Educators Alliance, which supports educators through its Teacher Wellness Fellowship.

He explains that the cohorts meet monthly on Saturdays for about 2 hours and talk about personal wellness and what it means for their work. Teachers in the fellowship are additionally given a 30-minute monthly session with a Black therapist, a wellness day in December, and a stipend to spend on a mini-vacation alone or with their families.

“All of the folks who’ve been in our program, 100% have retained their presence in the schools. And a lot of them talk about the fact that if ‘I didn’t have this support, I don’t know what I would be doing,’” Lewis says.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Dr. Micia Mosely’s name.

Rebekah Sager is an award-winning journalist and published author with over a decade of experience. Her work has been published in The Washington Post, The Hollywood Reporter, Playboy, VICE, Cosmopolitan, The Los Angeles Times, and more. She currently works as a reproductive rights reporter at the American Independent.

This story was supported by the Rosalynn Carter Fellowship for Mental Health Journalism, where Rebekah is a 2022-2023 fellow. Read her first story here.